This discussion between myself and Niamh Thornton took place through Skype instant messages on Friday 7th February. Our aim with this conversation was to expand on our previous blog posts.

[09:42:41] Niamh: In your blog I was really interested in the shared use of the media as a motif. In Pacific Rim TV news is used as a form of commentary and economical mode of storytelling. In Bordertown and the Virgin of Juarez the female protagonists are both journalists.

[09:45:12] Fiona Noble: It’s really striking that this is a feature shared by the films we are both working on – and I don’t think that this is exclusive to these films.

[09:45:43] Niamh: Do you think that it’s about telling stories about disenfranchised others in the films you are writing about?

[09:46:14] Fiona Noble: I can think of other examples in the Spanish context which include media reporting/representation as a visual motif – Las cartas de Alou springs immediately to mind but there are many others.

[09:47:29] Fiona Noble: Yes, I think on the one hand there is as you say the need to tell the other’s story.

[09:47:38] Niamh: In films and literature about Juarez it is a repeated trope. Frequently, they are journalists from outside (US, Spain, UK…).

[09:48:23] Fiona Noble: So, it is the external other who tells the story, who has the voice?

[09:48:54] Niamh: Yes, and the power to go above the local strictures.

[09:49:42] Fiona Noble: I think this provides a point of contrast then between the films/contexts we are working with – it is usually the Spanish characters who are journalists in the films I’m working on.

[09:49:58] Niamh: There is an important Mexican female journalist character (likely based on a real individual) in Bordertown who provides valuable information. But, the film is still focused on an Other as victim.

[09:50:43] Fiona Noble: Ilegal is the perfect example of this – protagonists Luis and Sofia are a journalist and private inspector, respectively. The plot places them in a position similar to that of an illegal immigrant, and so seems to expect us to empathise.

[09:51:28] Niamh: Is the assumption that we wouldn’t empathise if we followed the story of one of migrants?

[09:51:55] Fiona Noble: It seems that way – at least that is how the film has been read by others (i.e. Santiago Fouz Hernandez).

[09:52:36] Niamh: There are films that do take that position, though. Is that not the case?

[09:52:57] Fiona Noble: A more empathetic/sympathetic portrait of immigrant experience, you mean?

[09:53:12] Niamh: A more subjective one

[09:53:32] Fiona Noble: Yes, I think that’s what I was trying to map out in my original post.

[09:54:03] Fiona Noble: Ilegal is now ten years old – the more recent Retorno a Hansala seems to gesture towards a more subjective representation of immigrant experience.

[09:54:35] Niamh: Do you think that this trope of outsider experiencing/witnessing these events is successful?

[09:55:01] Fiona Noble: I think it can be.

[09:55:24] Fiona Noble: In the Spanish case, most films about immigrants/immigration are not made by those who have direct experience of this phenomenon (Santiago Zannou is the only director I know of who is a second-generation Spaniard, whose parents were African immigrants). So, I think to have this outsider framework can show a certain degree of respect for the distance between director/production team and topic.

[09:56:39] Niamh: Necessarily?

[09:56:54] Fiona Noble: That said, I think it can also be an extremely risky strategy – as in Ilegal where the immigrants are mere secondary characters, barely glimpsed in the background, while the Spanish protagonists take centre stage. What are your thoughts on this? How does it play out in the films you are working on?

[10:01:45] Niamh: I agree. That is often the case with Juarez. In the films on Juarez the victims are often multiply marked as others: working class, indigenous, country girls vs urban, cosmopolitan, middle class journalists. Also, the victims are to be read as “good” victims i.e. religious (sometimes to the point of superstition), virginal and innocent. They have none of the messiness of “bad” behaviour of real life. How does that play in terms of the immigrants you consider?

[10:06:32] Fiona Noble: It varies. In Ilegal we are offered next to no information about the immigrants who are the victims of persecution/ill treatment/death. They are illegal immigrants who are smuggled into the country. This is all we know. Retorno takes a slightly different approach: it begins with an unidentified illegal immigrant drowning. The film then follows legal Moroccan immigrant Leila and her attempt to come to terms with the death of her brother Rachid while attempting to make the crossing to Spain from Morocco.

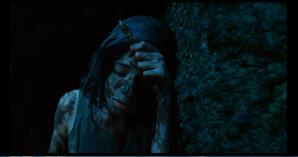

[10:08:51] Niamh: In both films about Juarez the women survive being left for dead and arise from the grave in ways that are reminiscent of horror films.

[10:09:59] Fiona Noble: And, is it indicated that their “good” characters has something to do with their survival? Is this a sort of triumph over evil?

[10:11:26] Niamh: It does appear to be. They are deserving of re-birth/second chance. But, their “goodness” and naïveté means that they must be protected by these stronger US women.

[10:12:13] Fiona Noble: So, we’re back into the hegemonic conceptualisations of self/other that we spoke about before.

[10:12:30] Niamh: Yes, no doubt. I suppose, now the question arises whether we are comparing like with like? Is there something unique about the migrant story and its tropes and can we talk about violence and its ethics alongside films about other themes? That being said, the border looms large in the Juarez film and there is some crossing of it by the privileged journalist and the victims. This might take us back to thinking about violence and how we write about its representation on screen. Can we have common strategies when writing about violence?

[10:16:08] Fiona Noble: I think this is an excellent point – one of the things I’ve been thinking about in response to our dialogue has been about the cultural specificity of violence. In your post you talked about having to make ‘multidisciplinary borrowings’, and, I wonder, to what extent we can compare the films/contexts we are working on?

[10:18:33] Niamh: Considerably, it would seem. But, also, it’s necessary to return to context and specifics.

[10:19:43] Fiona Noble: It certainly seems that our films share a similar visual grammar.

[10:20:39] Niamh: Yes. It can be useful to have tools from other contexts to use. Do you think that Spanish filmmakers pay much attention to the Mexican-US border narrative?

[10:21:33] Fiona Noble: That’s a really interesting point. Off the top of my head, I can’t think of any specific examples where other border discourses come into play in Spanish films about immigrants/immigration.

[10:22:18] Niamh: I suppose it’s difficult to tell unless a filmmaker expressly lays claims to influences.

[10:22:41] Fiona Noble: I guess. The example that springs to mind is Inarritu’s Biutiful.

[10:23:15] Fiona Noble: This film does situate contemporary immigration in Spain within a wider, global context. Although the link to Mexico is more historical than current – indexing Republican exile to Mexico in Spanish Civil War through Uxbal’s father.

[10:24:25] Niamh: Yes. There is that film which has 3 stories: one in Mexico-US, the other in Cuba and the third in Morocco. I can’t remember the name.

[10:24:39] Fiona Noble: Babel?

[10:25:27] Niamh: No. But that is an interesting example of the wider context and linked global experiences

[10:26:05] Fiona Noble: I’m not sure of the one you mean.

[10:26:28] Fiona Noble: But, it sounds like it would be an interesting one for both of us.

[10:27:29] Niamh: Just found it online, Al otro lado. Yes, because one of the stories is about a child going from Morocco to Spain. All of the migrants are young children and therefore necessarily sympathetic.

[10:28:05] Fiona Noble: Title sounds familiar – will check it out. I wonder if there’s a distinction to be made when events are based largely/primarily on fictional narratives (Pacific Rim) and when they are based on real events (such as the Juarez films). How does the treatment of violence differ in these contexts? You did talk about this in your post, but I wondered if we should elaborate on this.

[10:29:16] Niamh: It’s interesting because the distinction is about intention, but not necessarily about visual grammar. For example, Pacific Rim is very deliberately about spectacle in a way that would be tasteless if it were about a real event.

The violence inflicted on the women in Bordertown, for example, is ridiculous, because it seems that the director fails in making it convincing although his intention is to be sensitive. In the key attempted murder scene the woman is being strangled by a man who is raping her. He has his face contorted in ways that are exaggeratedly grotesque, while her face is acting “real” anguish. The problem is that a woman’s body on screen is always already objectified, so in an attempt to avoid this we are shown the violence either in long shot or the camera lingers on her pained and tearful face, and his grotesque expression, but the contrast between their performative styles in this one is jarring. Consequently, for me, it is unsuccessful.

[10:36:07] Fiona Noble: Which brings us back to the points you made at the beginning of your original post – about the difficulty of representing/writing about onscreen violence. That is, in spite of its prevalence.

[10:37:27] Niamh: Yes. Do we have new conclusions from today’s discussion, I wonder?

[10:37:45] Fiona Noble: Or more questions?

[10:38:15] Fiona Noble: I think we have ascertained that the films we are working on, in spite of their distinct production contexts/subject matters, share a certain visual grammar.

[10:38:18] Niamh: Which can be more productive in ways…

[10:38:28] Fiona Noble: Absolutely.

[10:38:57] Niamh: This is true. Also, we are still convinced that multiple tools are required to analyse these. Context can never be forgotten, but should not limit comparisons.

[10:39:41] Fiona Noble: I agree. And, we’ve also talked about the relationship between subjectivity and mass media across the distinct contexts, and the various possibilities/problems that this framework offers.

[10:40:39] Niamh: All worthwhile. It’s been good chatting about this. I certainly find it useful to know the commonalities and differences.

[10:42:51] Fiona Noble: I completely agree. Much definitely remains to be said not only about the complexities of representing violence onscreen, but also about scholarly approaches to the topic. The fodder of future blog posts and Twitter exchanges, I’m sure.